Module Views

2025-10-02

Module Structures

Structures

If you recall, we talked about the types of structures that exist in the Blue Bridge project.

This was because our definition of software architecture was the “set of structures that are needed to reason about the system”.

A structure is a set of components, relationships, and properties of both.

In other words, we could think about representing a structure with a typed graph. And indeed, most architecture documents show some flavour of a typed graph (‘boxes and lines’).

What is important, of course, is what those components, relationships, and properties look like. In this course we will put fairly strict constraints on what can be in a given structure.

What is allowed and not allowed defines what type of reasoning we can conduct.

We can also think about a structure as view on a particular system. Depending on our perspective, the views can be defined to show different information (just like a database). For software, what we want to show will be informed by what we care about. Typically, this is to answer questions like:

- what is going on when the system is running?

- how do we organize the code to work on it?

- what pieces need building first?

- how does it handle my requirements?

- what parts are from other vendors?

- how do I deploy this?

- what types of hardware demands does the system have?

- how does it manage security?

- how fast is it running?

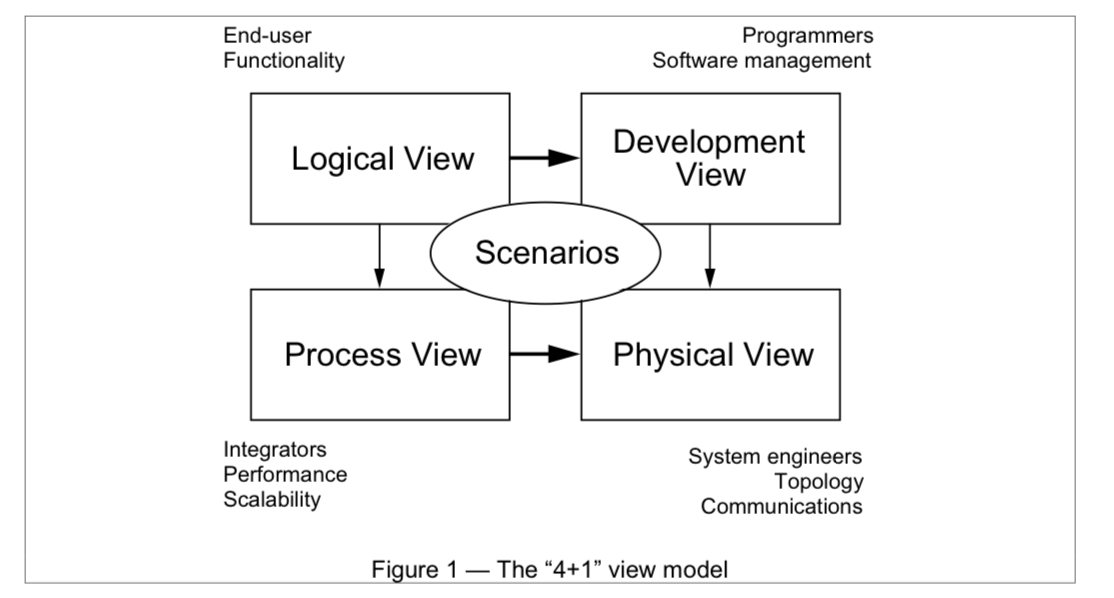

Other types of “views” - 4+1 Views

(Philippe Kruchten, UBC/Rational)

In the Rational 4+1 views model, we see a constrained set of views that tell us what exactly we ought to care about as developers.

- A logical view showing the object oriented structure of the design

- A process view, showing us concurrency and runtime behavior

- A physical view, showing how the software gets mapped onto hardware.

- A development view, showing how the code is structured for developers.

Tying these together is a scenario view that captures key system use cases.

Rozanski and Woods

Rozanski and Woods introduce the notion of viewpoints, which are similar to views.

- Functional, what functionality the system offers

- Information, how the system manages data

- Concurrency, how a system handles threads and processes

- Development, as above.

- Deployment, map the software onto hardware.

- Operational, how the system is managed in production.

These show very similar structures as the 4+1 model, with a difference being that RW are focused on ensuring that key stakeholder question are answered by the views chosen.

Both approaches are concerned with capturing information about the system that helps us answer our questions of interest (in our jargon, allowing us to show how the architecture satisfies key quality attribute scenarios).

Views/viewpoints are abstractions.

Each system must choose an instance of a view to show the elements specific to that system.

The particular arrangement of the elements may reflect the application of an architectural style; a common solution to a given problem (like a design pattern).

Types of Structures

In the textbook world, there are three key sets of structures we need to create views into, and reason about.

- Module Views

- Component and Connector Views (C&C)

- Allocation Views

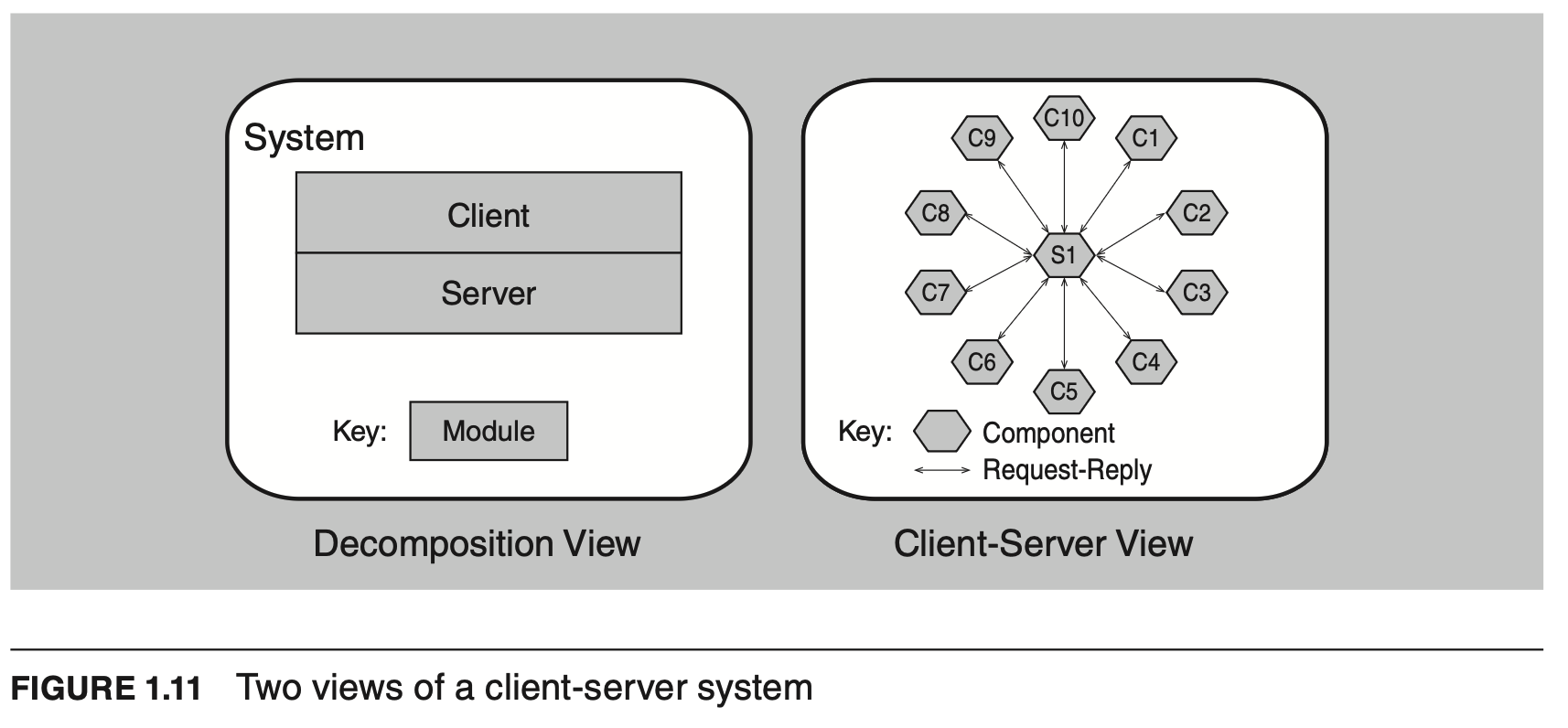

Two views

src: SAIP

Module structures capture a particular set of concerns we have about the system. They map to RW Functional, Informational, and Development viewpoints.

They map to Logical and Development views in the 4+1 model.

We’ll focus on the first two for now; I’ll talk about allocation views more when we discuss capturing operations.

Reasoning

- We reason about our system using its structures. There are 3 main view types with different views possible in each.

- A view reflects a particular structure of interest;

- a view may be composed of different styles.

- Each style imposes constraints on the view topology (e.g. no circular relationships) and relevant properties (always name, but perhaps strength of relationship, responsibilities, etc.)

Capturing the Architecture

A system’s documentation will consist of some instances of the 3 view types, plus some information that ties the views together.

We should be able to answer questions about quality attribute scenarios using the documentation package we provided.

In other words, with only this set of documents, you should be able to answer all the technical questions that e.g. the CIO might have for you.

Module Views (p. 332 of SAIP)

We use the following to structure our discussion about architectural views:

Elements: modules, implementation units of software with a coherent set of responsibilities.

Relations: typically part of, depends on, is-a

Usage: change impact analysis, incremental development, work assignment, information structures

Why We Care - analysis questions Module views can answer

- Construction blueprints

- Analysis of impact and changes

- Project management

- Onboarding

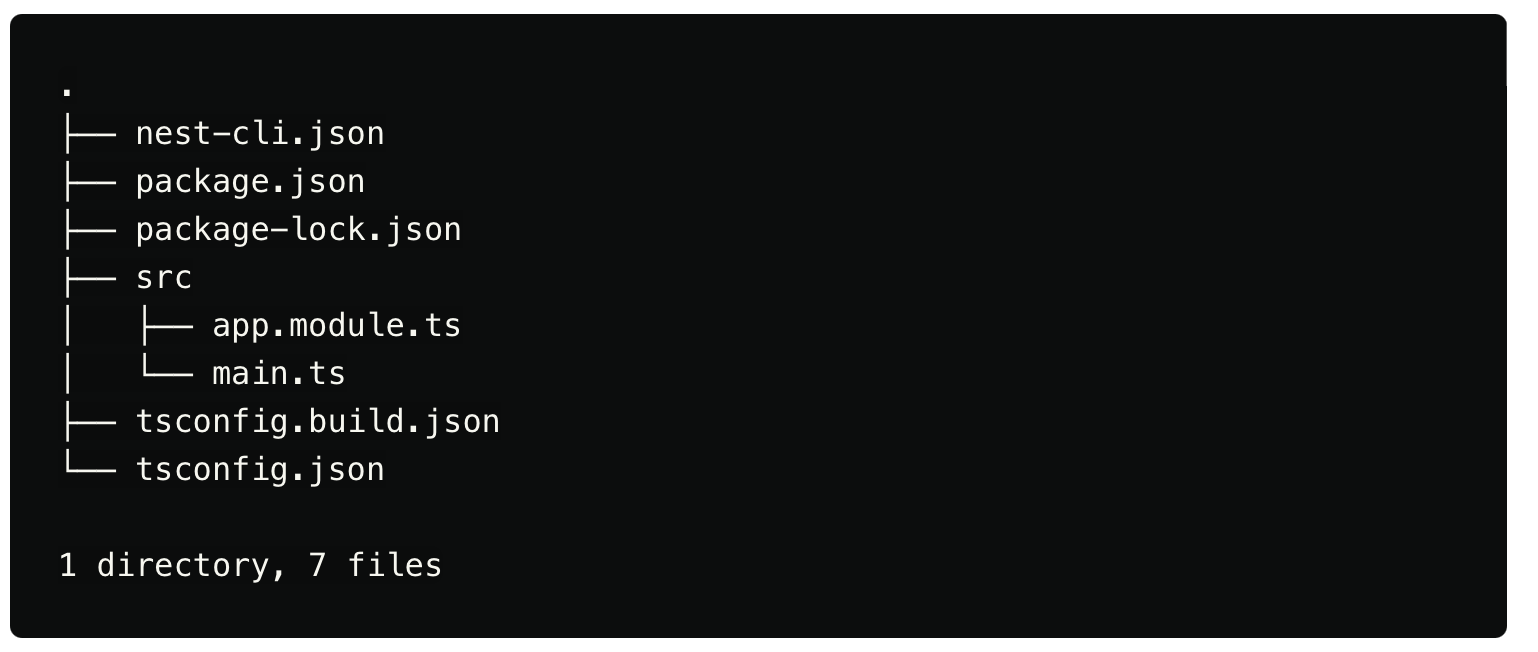

What is this?

Instances of Module Views - Styles

- Layers

- Uses

- Generalization

- Data Models

- and others

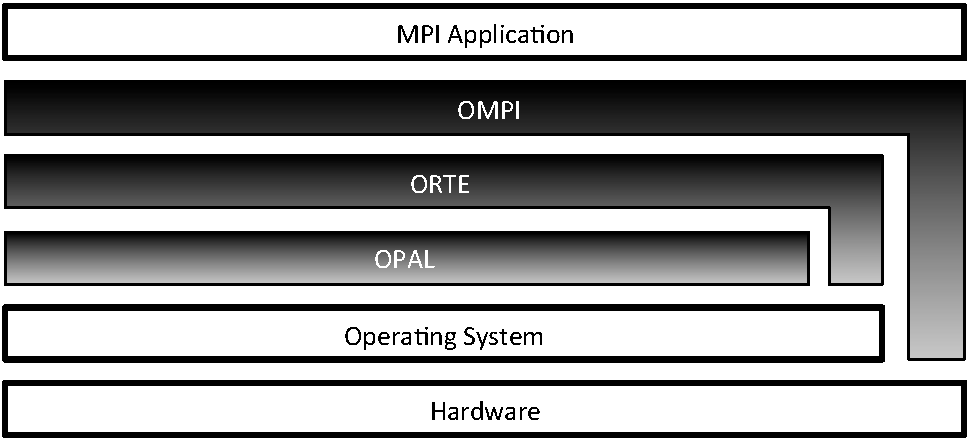

Layered Style

Show the permitted relationships between modules. A common overview for showing system context.

Elements: layers

Relations: “allowed to use” (A uses B if A depends on B’s correct functioning)

Constraints: software in exactly one layer; software can only use software in a(ny) lower layer

Layer example from OpenMPI

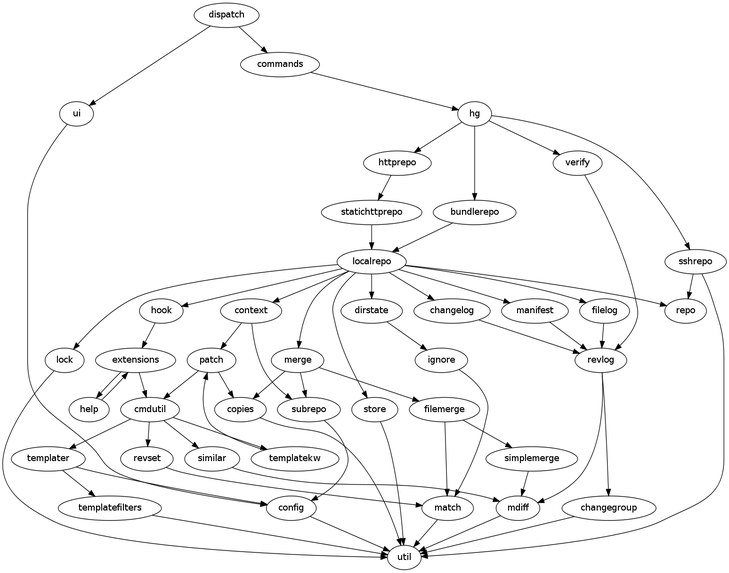

Uses Style

Tells the developer what other modules must exist for this portion of the system to work correctly.

- Planning incremental development

- Debugging and testing

- Change impact analysis

- Supply chain and software BOM analysis

Elements: modules

Relations: “uses”

Constraints: None.

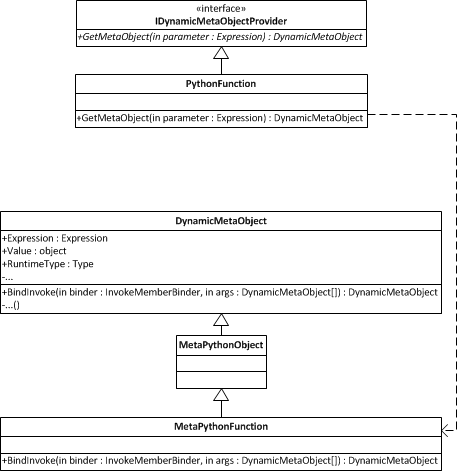

Generalization Style

The classic object model or class diagram notation. Captures commonalities, reuse opportunities, system organization. Describe data structures, communicate with possibly separate DBA team, help with domain analysis, help with module implementation.

Elements: modules

Relations: ‘is-a’

Constraints: number of parents, no cycles

DLR and Iron* runtime

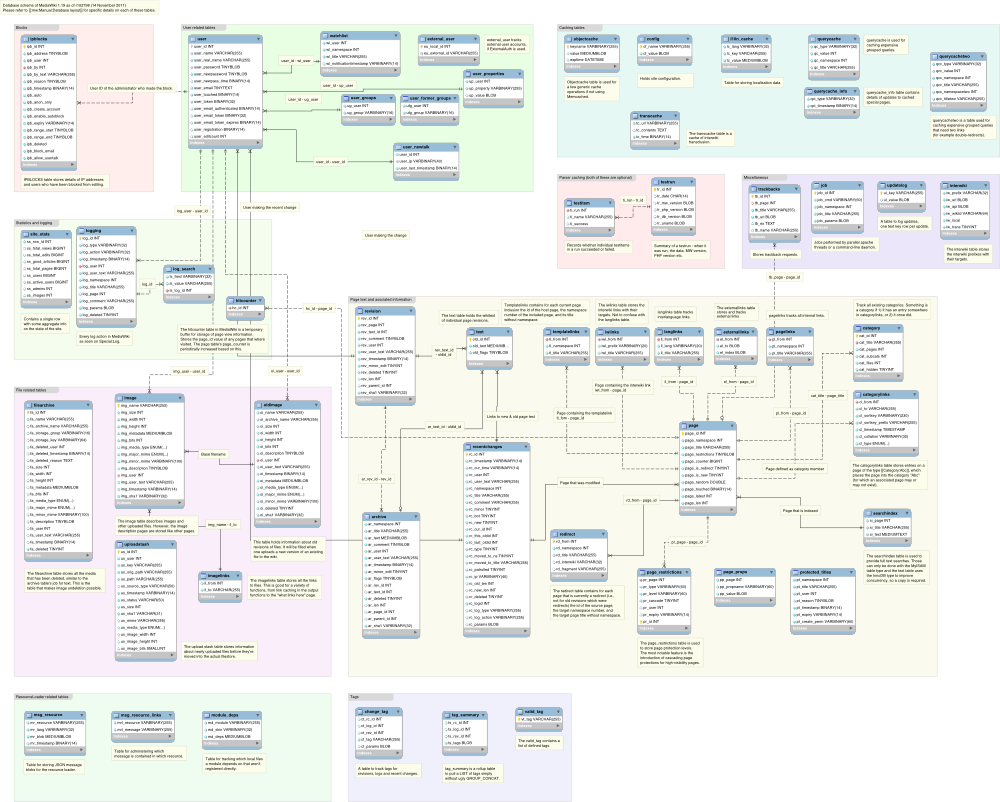

Data Model Style

Models important data entities and the relations among them. Classic SENG370 or SQL ER diagrams are data model styles.

Elements: Data entity representing data to be stored in system.

Relations: 1:1, 1:*, etc.

Constraints: normalization

Mediawiki Data Schema

Styles vs Patterns

An architectural style is an encapsulation of a solution to a problem.

Unlike a “pattern”, we usually think of a “style” as just capturing the solution, without the problem context.

You can find styles in a variety of ways: videos of conference talks (e.g., CQRS), style catalogs (PoSA), and blog posts.

The styles we will talk about in this course are pure instances of a style; in reality, a view will often combine different styles e.g. showing decomposition within layers.

Summary

- Module views help us understand the static, implementation-time architecture of the system.

- There are various styles that represent a module view, such as layering.

- Module views support questions about impact analysis, data structures, and development work set up.

Neil Ernst ©️ 2024-5