What Is Technical Debt

Initial Definition

“Shipping first time code is like going into debt. A little debt speeds development so long as it is paid back promptly with a rewrite… The danger occurs when the debt is not repaid. Every minute spent on not-quite-right code counts as interest on that debt. Entire engineering organizations can be brought to a stand-still under the debt load of an unconsolidated implementation, object-oriented or otherwise.”

– Ward Cunningham, 1992

Current Views

Most recently technical debt is

- a term of art that captures an elegant, business-friendly way to communicate the importance of refactoring and maintaining software.

The definition I’ll use is the following:

Definition

Technical debt occurs when a design or construction approach is taken that’s expedient in the short term, but that creates a technical context that increases complexity and cost in the long term.

Examples

- Code has become very hard to change because of the foundation of poor quality legacy code

- The system cannot be tuned for optimal behavior because cross-cutting concerns such as maintainability have not been addressed strategically

- Knowledge of quality is lacking because testing has been cut short in the interest of time

Good TD

Again, in modern software process, incurring debt can be a good thing, if it means you ship software and meet deadlines.

For example, what is the value of a Valentine’s promotion that is released Feb 15?

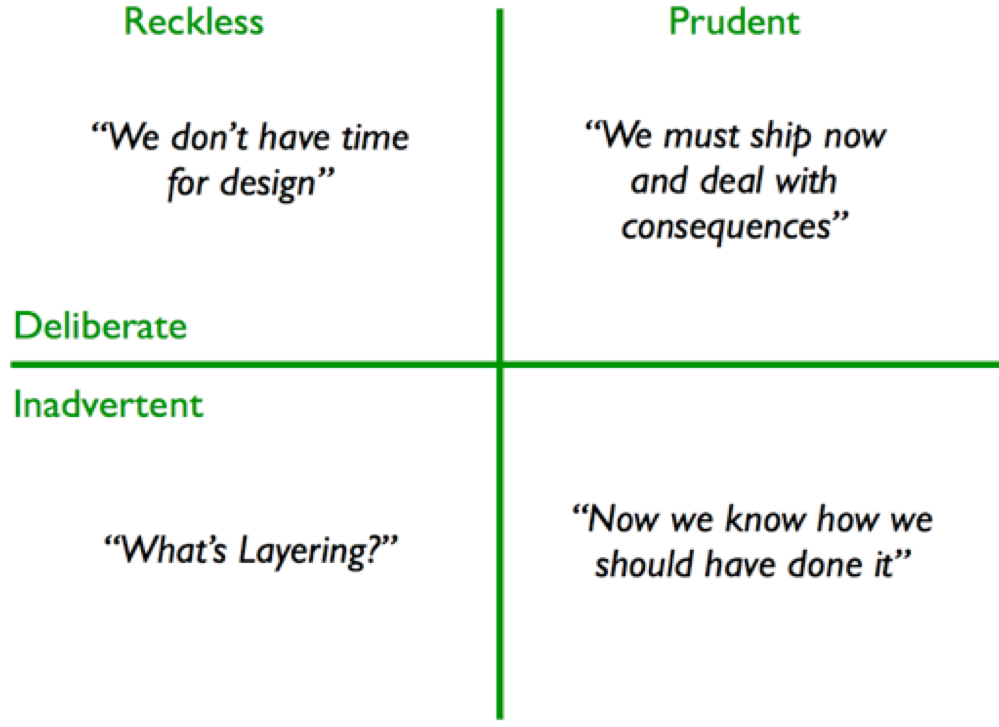

Fowler’s Quadrant

Martin Fowler has a quadrant that outlines this:

Managing Technical Debt

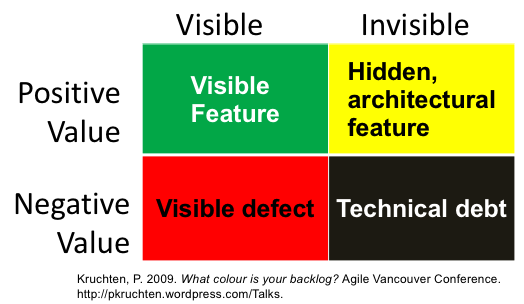

Philippe Kruchten (UBC, Rational Software) has a nice conceptualization of the role technical debt plays in software development.

Kruchten

TD is seen as an invisible, negative value for your code. Again, in the extremely short term TD is not bad. It become bad as time passes and the debt accrues.

We call the impact of accrued debt interest, which refers to the ongoing added costs you have to pay.

This can be in terms of longer release times, longer test runs, cognitive burden on developers, or other measures of impedance caused by imperfect code.

Managing Technical Debt

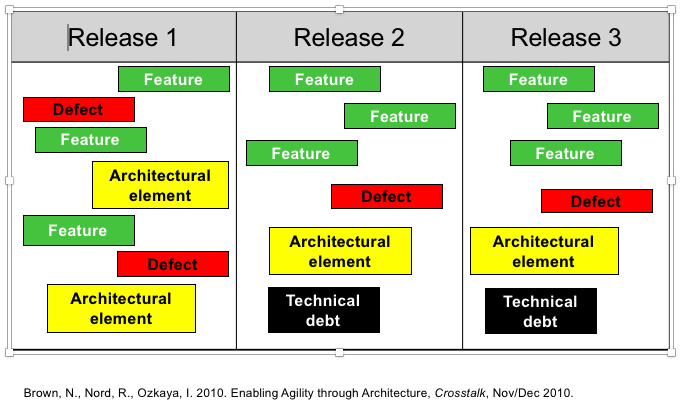

Managing technical debt comes down to two things.

- Visibility. It is essential to track the TD you incur at the time you incur it. Otherwise, it festers in silence. Like any bug, sunlight will kill it.

- Allocating money. Once you know it exists, you need to pay it off. Include TD in rational iteration planning process.

Managing TD

This can be as simple as changing a variable name, or as complex as adding or removing files and classes (if the ‘refactoring’ turns into something more complex, it is really about re-architecting, and deserves different treatment, unless your codebase and devops infrastructures are really solid).

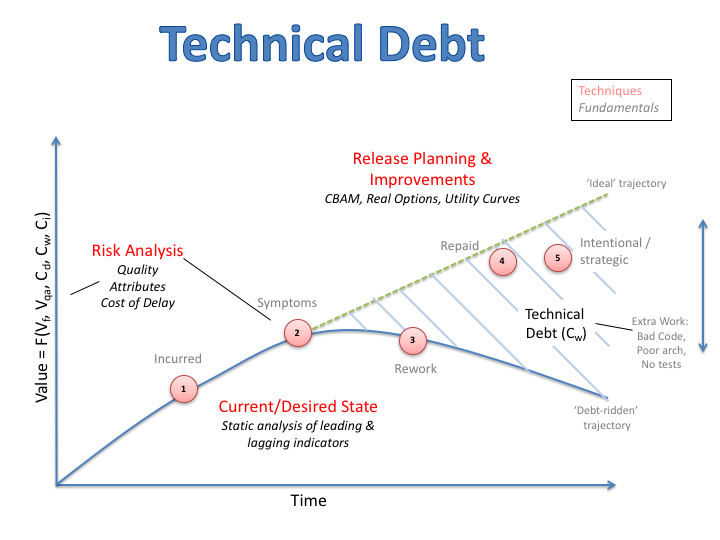

Planning for TD

TD over time

The following chart shows how we might see TD as a ‘drift’ between some ideal state (high value) and the actual state.

Code Quality and TD

Finding TD

How do you find technical debt? Kruchten argues for explicitly tracking the debt.

However, in many cases the debt has been incurred a long time ago, and all you know now is that things suck (high interest costs).

Bad Practice – Smells – in Code

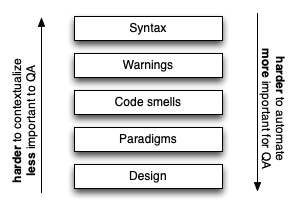

There is a continuum of “bad practices” from the code level up to the design level.

Tools can capture many of these.

But as we move ‘down’ the taxonomy, the clarity of the violation is reduced (harder to justify), and the ability for a tool to detect it becomes harder.

Think about how one might catch a buffer overflow error, vs designing code that doesn’t even use array indices.

Taxonomy

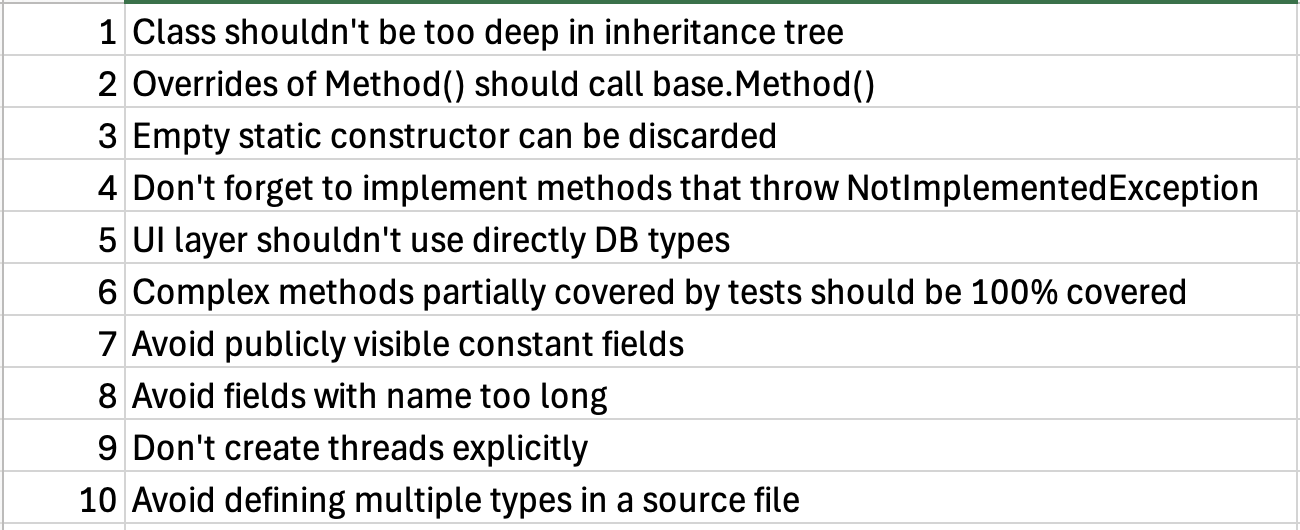

Exercise: What is TD?

- I have created a list of rules from a common design and code quality checker.

- classify each rule into one of three buckets:

- code-level problem

- paradigm problem (OO, Functional, Performance…)

- design/arch problem

Exercise

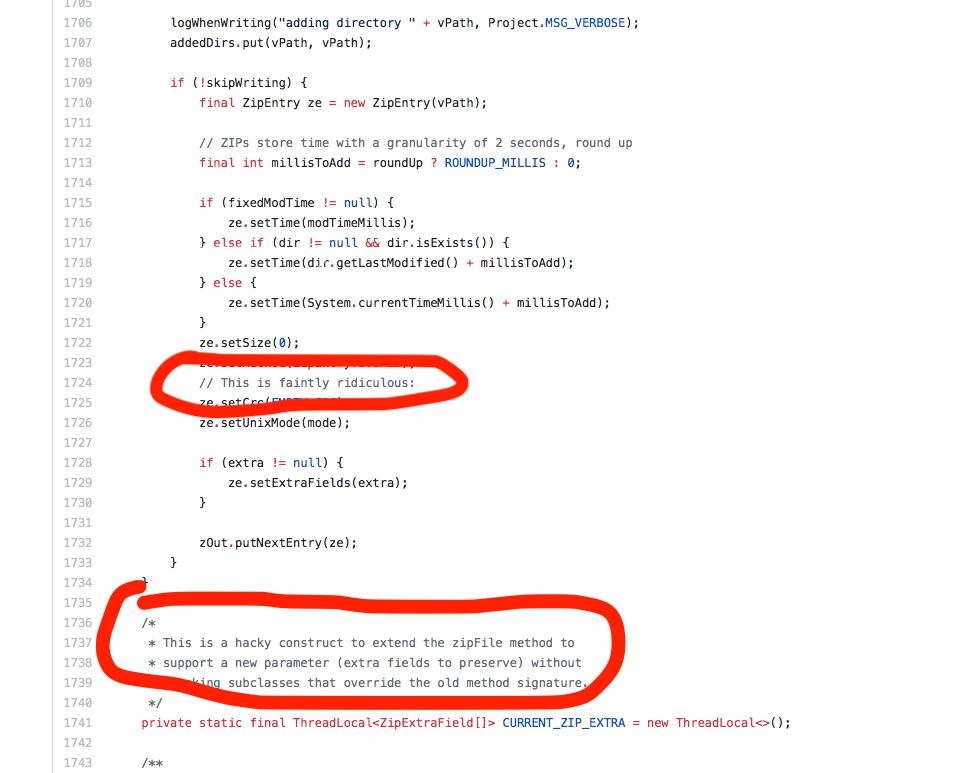

SATD

Self-admitted technical debt (SATD) is a term coined by Emad Shihab to capture comments in the code that ‘admit’ that a particular approach is a hack, or poor form.

In some cases it might be captured in a tool, but it is unlikely. They aren’t bugs; the code works. Just not as ideal as one might hope.

Grepping for these comments can be a good way to find TD. Just ensure it is architecturally interesting. The obvious downside is some code style guides explicitly frown on these types of comments.

Finding Smells

Some examples of tools include linters like Pylint, code smell analysis tools like Findbugs, and the platform analysis tools (which incorporate all sorts of analyses) like SonarQube and Codescene.

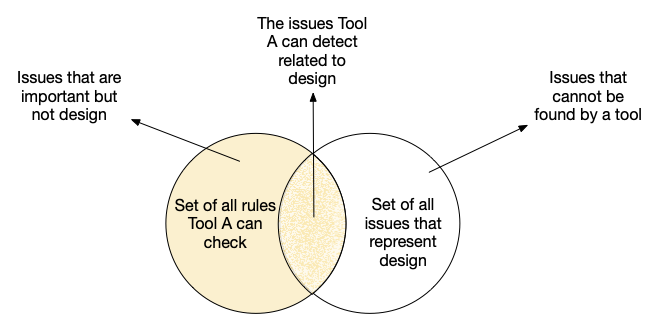

At the end of the day, as a tool user, you should keep the following in mind:

toolvssmell

Wrapping Up

- Technical Debt refers to shortcuts taken in system design, implementation, and deployment.

- SATD refers to explicit acknowledgement of sub-optimal practices in the source code.

- Incurring TD is part of learning what the actual “theory” of the software should be.

- Refactoring and rearchitecting the system to remove TD is an important part of maintenance.

Links

- UBER’s NEAL tool to do linting for their code

- Coverity’s lessons on static analysis

Neil Ernst ©️ 2024-5